Introduction: Defining Graffiti

Is graffiti an act of vandalism, a form of elite art challenging authority, or simply a raw expression of self that says: “I exist”?

Graffiti is one of the most prominent urban art forms in the modern era. What began as an underground movement led by anonymous youth has evolved into a global phenomenon-part artistic practice, part social commentary, and in some cases, even officially commissioned work. From New York to Tehran, from Tel Aviv to Berlin, concrete walls have become vast canvases for visual dialogue-personal, political, social, and aesthetic.

While this blog has documented graffiti and urban art worldwide for years, this is the first time a clear, structured guide has been published here to answer the essential questions:

What is graffiti?

What are its historical roots?

Which techniques define it?

How is it different from street art?

This in-depth guide is based on years of research, field documentation, and accumulated knowledge. We explore the difference between a tag and a piece, the rise of female graffiti artists, the legal dilemmas, and how graffiti lives today in the digital arena.

This isn’t just a guide-it’s a gateway to a vibrant, sophisticated, and often rebellious world where letters, words, and visuals tell the story of their creators, the space they occupy, and the society surrounding them.

The History of Graffiti

From Ancient Walls to Modern Cities

Graffiti didn’t emerge only in the 20th century. In ancient Rome and Pompeii, we already find carved inscriptions on public walls. But the modern form we recognize today was born in the streets of 1960s-70s New York, as a socio-cultural response by youth from marginalized neighborhoods.

The first widely recognized tag was Taki183, a Greek-American teen who wrote his name and street number across walls and subways. His actions sparked a movement-young people began tagging as a form of personal visibility in a society that overlooked them.

Graffiti & Hip-Hop: A Shared Origin

Graffiti developed in parallel with the rise of hip-hop culture, also born in New York’s streets in the ’70s. Hip-hop is not just music-it includes four foundational elements:

DJing | MCing (rap) | B-boying (breakdancing) | Graffiti

Graffiti served as the visual arm of hip-hop. Like rap lyrics, graffiti expressed rage, pride, identity, and resilience. Many graffiti artists collaborated with rappers and DJs at street parties and on album covers. The visual language of graffiti-with its dynamic and explosive forms-melded naturally with hip-hop’s rhythm and spirit of rebellion, making them twin pillars of urban counterculture.

Graffiti vs. Street Art: What’s the Difference?

The terms graffiti and street art are often confused. Both exist in the public realm, use urban walls as canvas, and share similar tools. But their intentions and cultural roots differ significantly.

Graffiti is primarily a personal act-a desire to mark presence, assert identity, and earn respect within the graffiti writer community. It centers on tags, abstract lettering, and internal language understood by fellow writers. The target audience is not the general public but other graffiti artists.

Street Art, on the other hand, is usually created for broader audiences. It is more aesthetic, accessible, and message-driven, often produced with public or institutional approval. It may include murals, figurative imagery, stencils, installations, or stickers, and frequently carries political, poetic, or social themes.

Key Differences:

| Graffiti | Street Art |

|---|---|

| Tags, stylized letters | Figurative images, murals |

| Internal language | Public-facing communication |

| Often unsanctioned | Sometimes commissioned or legal |

| Underground subculture | Accepted part of public space |

The Language of Graffiti: Techniques & Styles

Like any language, graffiti has its own alphabet, syntax, and dialects. It begins with the tag – the writer’s stylized signature, often illegible to outsiders but instantly recognizable within the scene.

From there, writers evolve into:

Throw-ups: quick, bubble-style graffiti with color

Pieces: elaborate, time-consuming artworks with detail and flair

Complementary forms include:

Characters (illustrated figures)

Stencils

Paste-ups (manual or printed)

Sticker art

Each serves as a tool for identity, message delivery, and territorial expression.

Visual Analysis: Typography, Color, and Aesthetics

Graffiti is deeply visual. Writers develop their own typographic language, influenced by Cubism, Gothic, or Pop Art. Spray paint availability impacts color choices, but so does emotional intent-warm tones (red, orange) contrast with cold or metallic hues.

Even architectural elements of the wall-like cracks, textures, or surroundings-may be intentionally integrated into the design.

Gender & Graffiti: Women's Voices in a Male Space

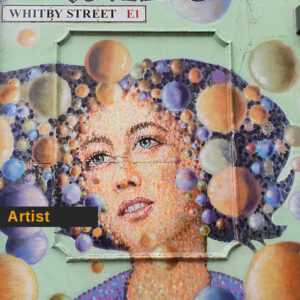

Traditionally, graffiti has been a male-dominated, heteronormative culture. Female street artists were sidelined or silenced. But in recent years, a distinct feminine presence has emerged.

International icons like Lady Pink, Miss Van, and Maya Hayuk, and Israeli artists like Nitzan Mintz, Hila Sheleg, Michal Rubin, Imaginary Duck, The Missk, and Dina Segev bring gender-conscious, personal, and political perspectives to graffiti. They’re not merely participants -they’re reshaping the visual language and cultural message.

Law and Graffiti: Vandalism or Art?

In many countries, graffiti writing is considered vandalism and treated as property damage. However, there are also cities that allocate designated walls, organize festivals, and even collaborate with artists.

The tension between law and creation creates a paradox: the same graffiti that is criminalized today may become a celebrated cultural landmark tomorrow. This raises discussions about freedom of expression, community identity, and the complex relationship between street art and the establishment.

Click here to read a detailed post on “Creators’ Rights in Street Art and Graffiti”.

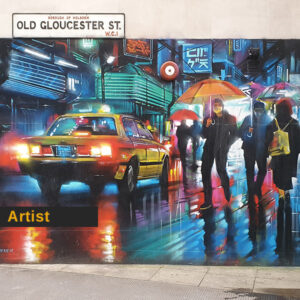

Graffiti as a Global Force

What began as spontaneous bursts of self-expression on the streets of New York in the 1970s has evolved into a worldwide phenomenon, transforming graffiti into a global cultural movement. From cities like New York, Berlin, Paris, Tel Aviv, São Paulo, Mexico City, and many others – graffiti has become an inseparable part of the urban landscape, expressing creativity, protest, and identity.

Graffiti transcends geographical, political, and cultural borders. In many cases, it reflects a direct response to the urban environment – often speaking a visual language of freedom, life, protest, and resistance. The development of styles, techniques, and artistic tools has revolutionized the medium, making it one of the most dynamic and innovative forms of visual expression in contemporary culture.

In Israel, graffiti culture began to flourish in the 1990s and has since become an integral part of the country’s artistic identity. Israeli walls are covered with vibrant works, fusing political, poetic, and personal narratives. The murals and tags reflect diverse social, cultural, and ideological layers, contributing to a rich and multifaceted Israeli street-art scene.

Summary – A Powerful Visual Language in Public Space

Graffiti is not just visual expression – it is a social, cultural, and artistic phenomenon with many layers. It thrives on city walls as an act of resistance, protest, identity, and community voice. Born out of rebellion against authority, alienation, social gaps, and lack of representation, graffiti has evolved into a language that bridges between personal freedom and urban narratives.

Graffiti’s Historical Roots

The history of graffiti traces back to the counterculture movements of the 1970s in the U.S., when young people began leaving marks on city walls. It developed alongside hip-hop culture, punk movements, political activism, and urban struggles for representation. From the walls of Paris in 1968 to the vibrant neighborhoods of New York, graffiti became a tool for marginalized groups to voice their reality, express identity, and challenge mainstream narratives.

From the Streets to Museums

What started as illegal markings on city walls has gradually gained recognition as a legitimate form of artistic expression. Today, graffiti and street art are celebrated worldwide: they are documented in books, presented in galleries, and showcased in international exhibitions. Many murals are now officially commissioned, while once-criminalized techniques are embraced by cultural institutions.

Graffiti Styles and Techniques

The graffiti world includes a wide variety of styles and techniques, such as:

Tags – artist signatures marking territory and identity.

Throw-ups – quick, large bubble-style letters, often using two colors.

Posters and Stickers – graphic interventions in the public space.

Stencils – precision-cut patterns enabling detailed, fast execution.

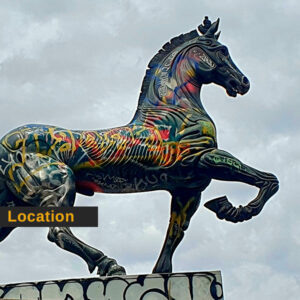

Murals – large-scale paintings that turn buildings into open-air galleries.

Each style carries its own codes, visual language, and artistic philosophy.

Graffiti in Israel

In Israel, graffiti culture has flourished since the 1990s, primarily in Tel Aviv, Haifa, Jerusalem, and Jaffa. The works reflect diverse influences – from political messages and poetic statements to environmental activism and personal storytelling. Today, Israel’s street art scene is vibrant and varied, connecting local culture with global trends and becoming a unique part of the country’s urban identity.

Graffiti as a Bridge Between Art and Society

Graffiti blurs the line between art and activism, between private ownership and public expression. It cannot be confined to museums or defined solely by commercial value. Rather, it challenges viewers to rethink their surroundings, raising questions about power, belonging, identity, and creativity.

An Ever-Evolving Phenomenon

Graffiti constantly evolves alongside society, technology, and urban life. From spray-painted walls and stencils to augmented-reality murals and AI-driven installations, it reinvents itself while staying rooted in resistance and freedom of expression. It is an inseparable part of contemporary visual culture and remains one of the most dynamic artistic languages of the 21st century